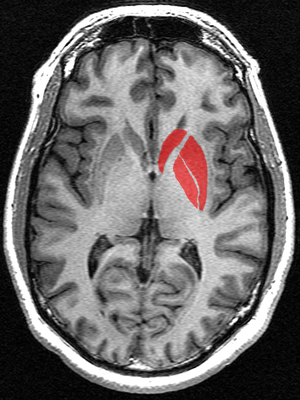

Though many scientists have focused on damage to a part of the brain called the striatum as a source of HD symptoms, this is a narrow picture of what changes in the brain during HD. A new book provides a summary of many research techniques over a hundred years that have led to a more complete image of HD as a disease affecting the entire brain.

A hundred years of Huntington’s history

When George Huntington first published his description of an inherited movement disorder in 1872, he summarized everything that was known about the disease in just a few paragraphs. Back then, this amounted to a concise and purely clinical picture that described chorea and other symptoms as well as their hereditary nature. If you’ve ever wondered why HD was named after Huntington, it’s not because he was the first to discover or describe it – he was just the first to report it to a wide medical community with precision and compassion.

Almost 150 years later, searching for “Huntington’s disease” on a scientific database yields tens of thousands of publications. There’s an enormous amount we now understand about the HD brain, from the invisible machinery in our cells, to the anatomical maps made possible by modern imaging. Since each doctor or researcher can tackle only a tiny section of the puzzle that is HD, it’s crucial to step back and look at how the picture is coming together. This type of synthesis happens all the time in science and is essential to how we move forward when we describe, investigate, and treat a disease.

Recently, four prominent HD researchers led by Udo Rüb put together a comprehensive review of literature (like an advanced textbook) summarizing the history of our knowledge about the human HD brain, from before George Huntington up to 2015. Covering more than a century of research on the anatomy and pathology of Huntington’s disease, their analysis suggests that HD affects much more of the brain than we usually talk about. This perspective will shape how doctors and researchers think about symptoms and treatment.